Philosopher Derek Parfit's "repugnant conclusion" is eminently plausible; but it is also false. Strictly speaking, the way to maximise aggregate and individual welfare is literally to fill up the Earth (and eventually the accessible universe) with sentient beings whose reward circuitry is radically enriched. Or maybe, ultimately, to launch a utilitronium shockwave. Population Ethics, Aggregate Welfare,

and the Repugnant Conclusion

“For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.”

Derek Parfit

(Reasons and Persons. 1984)

Naïvely, the most efficient method to maximise the happiness of the biosphere would be to develop forms of wireheading: direct stimulation of the reward centres of thousands of billions of mind/brains. Wireheading and its genetic and/or pharmacological analogues are energy-efficient and ecologically friendly. However, wireheading is also evolutionarily unstable - wireheads don’t seek to raise baby wireheads - and socially implausible. Such a scenario will not be explored here except to note how the wirehead option is an existence-proof that unlimited lifelong well-being is feasible in an arbitrarily confined space; pure pleasure shows no physiological tolerance. Actually, there is a complication. What used to be called the "pleasure centres" of the brain might better be called the "desire centres". Mesolimbic dopaminergic "wanting" is neurologically and anatomically distinct from mu opioidergic "liking". Intracranial self-stimulation studies demonstrate that desire, not pleasure, shows no physiological tolerance. But the term "wireheading" will here be used for an entire family of scenarios involving exclusively direct reward pathway stimulation: indiscriminate and undifferentiated pleasure without end.

There is an alternative to wireheading that is harder to dismiss. This alternative relies on the standard weak assumptions of population ethics harnessed to futuristic computational neuroscience. In theory, maximal aggregate and individual welfare - with no trade-off - can be achieved on the twin foundations of:

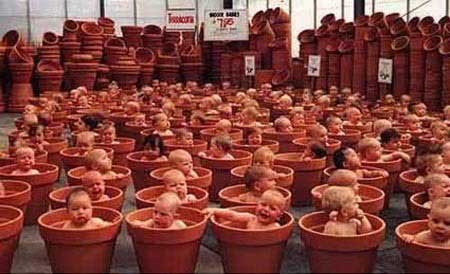

1) radical enrichment and recalibration of the reward circuitry of the CNS. Irrespective of population density, suffering can in principle be abolished in all sentient life; and mind/brains motivated entirely by gradients of cerebral bliss. Ultimately, superintelligent posthumans may be animated by gradients of well-being that are billions of times richer than the range of hedonic tone adaptive for Homo sapiens in the ancestral environment of adaptation.On this "Paradise Matrix" scenario of reward circuitry enrichment plus immersive VR, the Earth's pain-ridden ecosystems can be progressively dismantled [though virtual wildlife safaris will be optional]. Each envatted mind/brain/virtual world can dine on genetically-engineered single-celled total nutrition mix, subjectively tasting (perhaps) like the ambrosial food of the gods. In mature vatworld Matrix models, the carrying capacity of the Earth runs to thousands of billions of interconnected (post-)humans. Each of these thousands of billions can enjoy lifelong well-being orders of magnitude richer than anything possible today. To maximise aggregate welfare on a cosmic scale, vatworlds could eventually be dispatched to seed and superpopulate other planets in our Local Group of galaxies - and indeed anywhere habitable or more-or-less terra-formable within our light-cone, saturating the universe with positive value.2) a regime of global virtual reality, most memorably evoked in "The Matrix". The exponential growth of computer power (cf. Moore's Law) offers the prospect of lifelong immersive VR; a Matrix scenario minus its whimsical "Machines" dependent on pod-grown people for their bioelectrical energy. Most recently, Second Life and its cousins foreshadow what's possible. Next century's multimodal VR will be unimaginably more compelling.

For sure, this prospect sounds surreal. Vatworld paradise conjures up images from pulp science-fiction - and a reflex response of "that's just Brave New World". To philosophers, the story carries echoes of Cartesian demons, or more strictly Cartesian angels. Misleadingly, too, vatworld VR also raises the spectre of Harvard University professor Robert Nozick's "Experience Machine" argument. Nozick's thought-experiment purportedly refutes mental state welfarist theories by showing that we value - or at least think that we value - more than "mere" pleasurable experiences. Thus if given the chance to plug ourselves into a device that allows us to experience our fondest dreams-come-true, most of us would allegedly spurn the offer. This is because we value mind-independent truth, in some sense yet to be semantically elucidated. However, it should be stressed that global VR plus reward-pathway enhancement can permit an arbitrarily high degree of mutual realism in each computationally interconnected virtual world. For as sketched here, an immersive virtual reality regime can be interactive and consensual, not solipsistic. If you write a novel in immersive global VR, other people can read it. If you compose music, other people can enjoy it. If you want to chat with your friends, you can do so - just like now. What's different is that instead of literally hurtling around the world in planet-fouling cars and planes using the traditional musculature of extracranial bodies, our sensorimotor stimuli can be computer-generated instead via brain-computer interfaces.

Of course, in practice our hypothetical VR-living descendants may program and dwell in virtual worlds with different laws of physics from Darwinian primitives. Our successors may occupy different modes of consciousness. Their VR social structures will presumably be transformed to reflect post-scarcity economics. Post-humans may take advantage of their limitless morphological freedom to assume a protean array of different VR bodily guises, or none at all; and they may opt to live in exotic designer heavens of our own devising. But this diversity of virtual worlds is optional. An advocate of Nozick's Experience Machine argument can't rely on the prospect of such alternative world-building to defeat the superpopulation scenario set out here. For computer-maintained vatworlds aren't intrinsically any more or less escapist than the virtual worlds of conventionally enskulled brains. When combined with radical mood-enrichment, vatworlds allow immensely more populous and ultra-high quality life to flourish than the brutish ecological naturalism of evolutionary history. "Heavenly" virtual worlds are neither computationally more demanding nor neurologically more energy-hungry by nature than their "Hellish" or mediocre Darwinian counterparts.

Intuitively, one may still recoil from any such paradise vatworld proposal - even though aggregate and individual welfare will be maximised i.e. both the sum and distribution of well-being are optimal. One recoils because all manner of distasteful images are evoked, not Heaven-on-Earth. The conclusion drawn here may sound even more repugnant than Parfit's. However, computer-choreographed "vatworlds" are neither more nor less prison-cells than traditional vertebrate skulls. So we won't be any more "trapped" than we are now; and in practice, we may feel greatly empowered. The term "virtual" is unfortunate because it suggests the construction of an inferior simulacrum of Reality as we understand the mind-independent world at present. On the contrary, utopian computational neuroscience offers the prospect of overpowering verisimilitude, dynamism, and seemingly boundless Lebensraum. Tomorrow's VR universe need not feel "crowded", let alone claustrophobic, even as the packing density of its substrates is maximised to ensure the greatest welfare of the greatest number. Optionally, "the World" in VR can be rendered no less obstinately mind-independent than it appears today. Likewise, designer drugs and genetic engineering can optionally be exploited to enhance our sense of authenticity - the very opposite of the derealisation and depersonalisation endemic to urban mass society. Indeed with selective use of supernormal stimuli, everything desirable can feel "more real".

Vatworlds sound ethereal since they are "disembodied". But they can incorporate an arbitrarily high level of sensuality and archaic bodily functions, if so desired. As phantom limb and similar phenomena attest, extracranial bodies are dispensable; our somatosensory cortex can't directly access "its" extracranial body even as evolved "naturally" under a Darwinian regime of natural selection. The only bodies we ever know are "virtual" bodies, whether our own, encoded pre-eminently in the somatosensory cortex, or the avatars of our circle of acquaintance populating our organically-generated world-simulations.

The ethical assumptions underlying a Paradise-Matrix are modest and relatively uncontroversial. In the jargon of economics, a superpopulated VR vatworld scenario can be "Pareto-efficient" [Pareto-efficiency, aka Pareto-optimality, is a measure of efficiency in multi-criteria and multi-party situations. The Pareto criterion in welfare economics is normally regarded as morally undemanding. Yet the principle insists anything that can be done that would make at least one individual better off without making anyone worse off - a "Pareto improvement" or "Pareto optimization" - should be done.] Nonetheless the outcome of applying these modest assumptions violates our everyday intuitions - and the usual pieties of population ethics. So which ethical theories mandate this bizarre conclusion?

A super-populated Paradise-Matrix is seemingly entailed by rigorous application of "hedonistic" utilitronium shockwave” scenario, though its sociological credibility is moot. Either way, the negative utilitarian may be satisfied, too, since suffering is eliminated via rewriting the genome; the extra happiness yielded by the abundance of extra inhabitants of the universe is morally redundant but unobjectionable. The case of so-called preference utilitarianism is more complicated, since the term is something of an oxymoron [or at least a misnomer] given our existing multitude of ill-conceived preferences. But some kind of Paradise Matrix is mandated by most forms of preference utilitarianism too, since both the sum and distribution of satisfied preferences are potentially maximised.

A complication for the preference utilitarian is that if and when anything akin to this pan-VR scenario is ever seriously proposed by policy-makers, then some agents may form an explicit preference that their actions should be implemented via a traditionally routed causal chain rather than via the Matrix. Yet this newly explicit preference for grounding in basement reality is presumably of limited weight when set against the astronomically wonderful payoff, i.e. the superabundance of realised preferences of trillions of post-humans pursuing their life-projects in vatworlds. The causal chain in Paradise Matrix-based civilisations is non-standard, by our lights. But it is not a contrived or "deviant" causal chain, as in Gettier-like examples against knowledge-claims. Moreover a preference for traditional embodiment is arguably a selfish preference. If sustained, the status quo will extinguish or preclude life for myriad other potential sentient beings: classical bodily existence carries a lethal ecological footprint. Assuming traditional embodied lifestyles are retained, then the Earth can support only a few tens of billions of people at most; and the planet will paradoxically seem horribly crowded. By contrast, superpopulated VR vatworld scenarios permit maximal welfare [or satisfaction of preferences, etc] of the maximum number of people or post-humans (and perhaps their non-human animal companions). Standard population ethics is radically life-denying. We don't know the names of its victims, but they are legion.

"Welfare" here is left purposely ill-defined; the term is intended to embrace subjective well-being in the very richest sense for all sentient life. However, the notion of welfare isn't here tied specifically to utilitarian theory, even though non-utilitarians might view the sort of civilisation discussed in this fable as a reductio of applied utilitarian ethics. The construction of a Paradise Matrix isn't mandated by nonconsequentialist ethical theories (e.g. virtue ethics) that lack the motivating assumption of aggregate welfare-maximisation. But if, for example, you think aggregate and individual beauty [or whatever] should be maximised, then a "beauty Matrix" allied to aesthetic neural enrichment would maximise aggregate and individual beauty. Hybrid scenarios are possible too. The common feature of all these superpopulation models is that individual agents don't act out the contents of their egocentric virtual worlds independently of the Matrix; and their hedonic tone is pharmacologically and/or genetically enriched.

Yet a question naturally arises. Is the life of these thousands of billions of sublime vatworlds really valuable - "objectively" valuable as well as subjectively valuable? After all, the inhabitants of a Paradise Matrix are "merely" brains in vats (etc). But today we are "merely" brains in skulls. Is the value of life itself supposed to turn on a contingent historical distinction? Or on the metaphysics of perception? Either way, this discussion is intended only as an exploration of the disguised implications of the premises of standard welfarist population ethics. The Meaning of Life or a defence of ethical realism are topics best tackled elsewhere.

One may wonder whether any adventurous souls born into a hypothetical Paradise Matrix will ever wish to be unplugged. Perhaps an inquisitive philosopher wants better to understand the (post-)human predicament: confinement to "mere" stacks of mind/brains. By analogy, today a rare patient bound for the neurosurgical operating table might request that his or her brain-surgery under local anaesthesia be recorded on camera, confirming that s/he is really "just" a mind/brain/virtual world in a skull: just one skull-encased microcosm among billions. But for the most part such cranial inspection is unilluminating.

The technical challenges to developing VR vatworld civilisations are formidable by current standards. The story told here is notably light on details of the Transition from where we are now. So this fable certainly shouldn't be treated as a prediction. Yet the exponential growth of computing power could in theory deliver the computational resources to generate a rudimentary Matrix within a century or two; and biotech can deliver the reward pathway enhancements. Generating realistic virtual worlds for puny-minded Homo sapiens isn't unduly challenging for a mature civilisation since our visual world, for instance, is constructed from a mere 130,000,000 or so polygons a second. The technology needed is complex but not impossibly utopian. A global Paradise Matrix does not rely on speculative metaphysics or a hypothetical ontological revolution (cf. scanning, digitizing and "uploading" ourselves into inorganic computers, a potential recipe for zombies). But the timescale of any such revolution on Earth is of course unknown. Perhaps a Matrix will never take root; and the contrasting "empty world" regime entailed by traditional embodiment will persist indefinitely, with or without reward pathway enhancement.

So is this fable just an idle philosophers' thought-experiment designed to challenge our pre-reflective intuitions rather than serious science prophecy? Yes, quite possibly. For just who (or what) are the janitors of such a Paradise Matrix? Who are the sysadmins? Could the Matrix be hacked? Quis custodiet ipsos custodies? ["Who shall watch the watchers themselves?"]

Yet one reason such VR vatworld scenarios can't be excluded outright is that within a few centuries, we are likely to have conquered death and ageing. Thereafter our quasi-immortal descendants cannot procreate unchecked, not because superdense populations necessarily impair individual quality of life even if aggregate welfare is increased (Parfit's repugnant conclusion, aka the "mere addition paradox"), but because there is a physical limit to the number of mind/brains/virtual worlds that can be housed in a finite area - whether envatted or enskulled. On a cosmic scale, the Bekenstein bound presumably sets the ultimate limits to aggregate and individual welfare, at least within a given multiverse. We are unlikely to run up against this constraint in the near future. The calculation of cosmic utility functions is a task for mature superintelligence, not archaic humans - though it falls to archaic humans to create the preconditions for mature superintelligence.

Quantifying the well-being or life-satisfaction of a superpopulated biosphere is hard even assuming utopian neuroscanning techniques. The dilemmas of population ethics aren't eliminated altogether, even assuming some variant of the Paradise Matrix scenario outlined here. First, in order to maximise aggregate welfare it's unclear whether matter and energy should be configured to stack human-sized mind/brains/virtual worlds or alternatively to stack supersized posthuman mind/brains/virtual worlds. Anthropocentric bias aside, a single flourishing human mind/brain/virtual world is generally accounted superior by value theorists to 100,000 individually minimally conscious worms, say, even if aggregate vermal sentience is notionally greater. But by parity of reasoning, is a single post-human mega-mind/brain/virtual world individually much more valuable than a multitude of diminutive speckles of human sentience? If so, should transhuman population ethicists advocate conversion of the latter into the former? How? One complication is that it's unclear whether massively supersized brains can sustain unitary consciousness (unless the temporal depth of their here-and-nows vastly exceeds traditional human awareness). Despite this uncertainty, there is no reason to suppose that posthuman mind/brain/virtual worlds won't physically be hugely bigger than their human ancestors once we are liberated from the cognitively incapacitating constraints of the human birth-canal.

A further obstacle to the exact quantification of individual and aggregate welfare in Paradise Matrices lies in post-Everett quantum mechanics. Assuming universal QM, scenarios akin to some version of the superpopulated vatworlds mooted here are presumably real and physically inevitable in some branches of the multiverse; only their density in the universal wavefunction is unknown. Intuitively, their density/comparative frequency is extremely low. But the comparative abundance of sentient minds supported by such worlds relative to their sparsely populated counterparts makes it hard to be sure that living in a Paradise Matrix is atypical.

Should this wildly counter-intuitive implication be embraced by mainstream population ethics? Or should we revise our values on pain of inconsistency, supplementing our premises [i.e. maximise aggregate welfare without compromising individual welfare] with an ad hoc ban on vatworld-building? Perhaps so. Yet if we think our values are worth retaining, then it's irrational not to embrace their implications. Rationally, after mastering the technologies of invincible well-being, we should make the world a better place by creating additional happy lifeforms. Indeed unless one is a strict negative utilitarian, perhaps we have a moral obligation to do so.

Or alternatively, plan for a utilitronium shockwave.DCP (2007)

last updated 2025.

Resources

Utilitarianism

Future Opioids

BLTC Research

Utopian Surgery

Quantum Ethics?

Superhappiness?

High-Tech Jainism

The Wired Society

Social Media (2025)

The Good Drug Guide

Paradise-Engineering

Physicalistic Idealism

The Abolitionist Project

Quora Answers (2015-25)

The Hedonistic Imperative

Reprogramming Predators

The Reproductive Revolution

The Biointelligence Explosion

MDMA : Utopian Pharmacology

New Harvest: advancing meat substitutes

Critique of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World

"THE BRAIN is wider than the sky,

For, put them side by side,

The one the other will include

With ease, and you beside."

Emily Dickinson

dave@hedweb.com